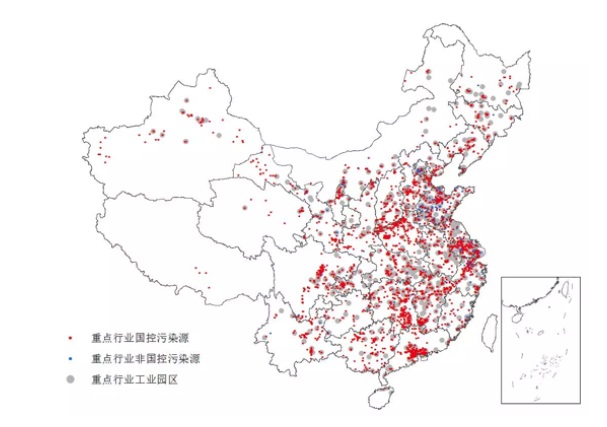

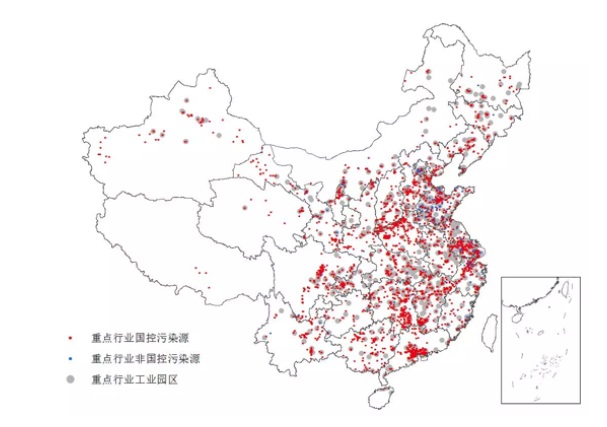

Map produced by filtering of pollution source data. Source: IPE

The Difficulties of Tackling Soil Pollution in China

Qing Yan

Chen Nengchang, senior researcher at the Guangdong Institute of Eco-environment and Soil Sciences, points out that for the last 30 years, there are three kinds of soil problem: soil erosion, soil pollution, and soil degradation. The last two problems are directly related to soil quality. Industrial development and urban construction have developed rapidly, however, environmental regulations and resolution measures are not well established, which made soil pollution become worse. In addition, a change of use of fertilizers (from organic fertilizers to chemical fertilizers), abuses of fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides, lots of plastic sheeting, among others, have caused soil deteriorating, high acidity, hardening, and the imbalance of nutrients and microorganisms. This has led to a series of problems such as the deteriorating quality of farm products, low production, and high amount of heavy metal.

Since 1994, the NPC Environmental and Resources Protection Committee has concerned with the legislation of prevention of soil pollution. In December 2004, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Ministry of Land and Resources issued a report on “Investigation of National Soil Quality and Specific Task of Preventing Pollution”. In early 2005, the Central government provided specific fund to support the task.

From April 2005 to December 2013, China has started the first investigation of national soil pollution. In April 2014, Communiqué of Investigation of National Soil Pollution was issued, which covered all arable land, parts of forestry, grassland, unused land, and construction land, with a total of around 6.3 million square kilometers. It stated that “in general, the situation of soil environment is not optimistic. Some regions of land are seriously polluted, the quality of arable land is terrible, waste land of industrial and mining areas are clearly problematic……The degree of soil pollution has four categories: slight pollution, 11.2%; light pollution, 2.3%; medium pollution, 1.5%; and serious pollution, 1.1%.......From the distribution of pollution, the land in the south is more serious than the north.”

In 2011, the news report of “The Cadmium-polluted Rice” aroused widespread concern about soil pollution and its legislation. On 28 May 2016, the State Council released Soil Pollution Prevention Action Plan, or “Ten Clauses on Soil” which clearly states that a worsening of soil pollution will be brought under initial control by 2020; and that soil quality nationwide will be stabilized or improved by 2030. By the middle of the century, China’s soil would be required to show an overall improvement. By the end of this decade, 90% of China’s polluted land (including arable land and other types) must be made safe to use, with that figure required to rise to 95% by 2030.

Lack of data

Chen Nengchang remarks that soil is rare and strategic resources, as well as the base of national and human livelihood. However, in the progress of development, we do not pay enough respects to soil; when we face the question of soil governance, we do not have basic understanding about soil. He explains that in principle, two questions should be taken into consideration: One, the degree of seriousness of soil pollution; second, the use of land after soil improvement. Soil is a highly imbalanced and complicated system. Firstly, we should conduct scientific analysis of soil structure, micro-organisms, among others. Based on the result, we should design different strategies and goals for different areas. Generally speaking, if the land is used for crop production and involved in human food chain, we should raise the standard of regulation. Now there is still room to improve soil management in respect of ecology. In actual cases, we should also consider ecological environment in specific areas, and the effects on specific food chain. In China, the current standard of soil quality was set in 1995. Although some standards are very loose (such as lead), it is the most rigid standard of the world (particularly cadmium and mercury).

He thinks that there are good suggestions of macro-framework of the Plan, for example, the establishment of surveillance network on soil pollution, different managements of arable land according to the degree of seriousness, reinforcement of protection of unpolluted land, among others. However, the key point is that there is lack of data about soil pollution, such as the scale of polluted land and their locations, the scale of polluted land with “safe use”. So he cannot predict the workload and the difficulty of feasibilities.

There are no accurate figures in the 2014 Communiqué so the reality of soil pollution is still unknown. After the incident of soil pollution at Changzhou Foreign Language College in April 2016, Chen Jining, the minister of Ministry of Environmental Protection, declared to conduct a comprehensive survey on national soil pollution. The first clause of “Ten Clauses on Soil” mentions the tasks to investigate the scale of polluted arable land, distribution, and the impacts on farm products before 2018; to identify the distributions of and environmental risks of polluted land caused by large enterprises before 2020.

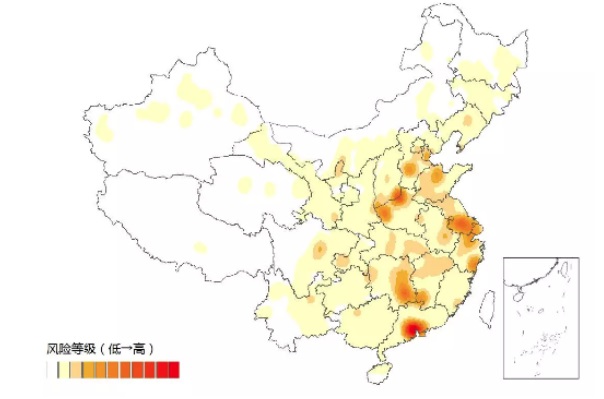

After the Changzhou scandal, the Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE) published a map of soil pollution risk – the first such map to be made available to the public in China. The IPE produced its map by filtering its pollution database, identifying 4,500 companies in 13 polluting industries such as chemicals, mining and metals. Of these, 3,998 were state-controlled and 502 non-state controlled, and 729 industrial zones home to the same industries. These locations were then marked on a map of China.

Map produced by filtering of pollution

source data. Source: IPE

Map of levels of risk, based on locations of 4,500 companies in key industries and over 700 industrial zones. Source: IP

Hugh costs of Improvement

Another challenge to soil improvement is the cost. Zhang Junjie, assistant professor at University of California, San Diego, argues that the Plan’s principles of “polluter pays” and lifetime liability for pollution should be made as powerful as those in the US Superfund law. However, the Plan does not specify what form that liability takes (on which companies should contribute to a clean-up fund, to hire a third party to carry out remedy) so further discussion is needed. Meanwhile, Ma Jun of IPE, is worried that the existing regulation, which makes the purchaser of a site liable for historical pollution, could be a loophole that companies could exploit if they are unable to deal with the problem. Existing regulations might also make it possible for companies to opt for bankruptcy and avoid paying for a big clean-up, which would require the government to step in.

The Heavy Metal Pollution Fund was set up in 2010 and has received billions of yuan in funding every year, with a sharp increase last year, to over 9 billion yuan (US$1.36 billion). However, that pot of cash is deemed insufficient to deal with the huge scale of the problem. This is tiny in comparison with the trillions of yuan that is needed to clean up soil pollution. The action plan calls for more government spending and the use of Public Private Partnerships, but as yet there are no specific programmes for doing this. Currently it is unclear to what degree the private sector will be involved.

Chen Huaiman, a well-known soil scientist and a senior researcher of Nanjing Soil Research Institute of China Academy of Sciences, remarks that only the government can put “Ten Clauses on Soil” into practice. He explains that the establishment of surveillance network of soil quality should be reliable to the grassroots units. Over the whole country, the Ministry of Environmental Protection has its surveillance units, the Ministry of Agriculture has its agro-environmental units and soil fertility units. The main issue is how they can implement their obligations and how they can join and work together. This is indeed a task of government.

In general, the seriously polluted land is seldom caused by peasants themselves. The origins of pollution are always due to factories or mining. The Government should make a compensation system that the government pays the right of land use and carries out the principle of “who pollutes, who pays”. Only the government can put the policy into effective use.

Sources:

(1) Well-known Soil Scientist Chen Huaiman: “Ten Clauses on Soil” are very accurate, but is there any problem of implementation?”, 4 June 2016, Soil Watch, quoted from Agricultural Environmental Sciences , 2 June 2016.

(2) Chang Chun, “ ‘Ten Clauses on Soil’ is issued, does it mean the problem is resolved?”, Chinadialogue , 14 June 2016.

(3) From “The Cadmium-polluted Rice” to “Ten Clauses on Soil”, 19 January 2016, Soil Watch, quoted from Landscape Design Studies (Volume 3, no. 6, 2015).